The course ‘Music and Social Change’ is being taught at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam by Loes Rusch. The content of this page has been gathered and formed by the students in the academic year 2023-2024.

Playlist:

Introduction

Music and social change

During the first semester of the academic year 2023-2024, three master students from the conservatorium van Amsterdam have been following the elective Music and Social Change taught by Loes Rusch.

In this elective all participating students have been challenged to research and present a topic of their choice that expands on how music can be relevant to social change. In short, the course has been diving into the domains of how music can be an agent of sociological changes, a commentary on power and a mirror of historical, political and cultural change. In addition the students have been researching the overlap between music, politics and spirituality.

All three participating students have been presenting their findings in front of each other, before opening a discussion on the material. For every session scientific resources have been used as the starting point of the research. In this article, the three students present summaries and reflections on the topics they have discussed with references to the academic writings they have been reading and researching.

Reflections

“Music is the most powerful art. It has the power to be remembered, the power to be performed, the power to influence and inspire. But, above all, it has the power to make statements; to comment on power, to express the exhaustion and outrage of the people, to fuel the crowd into making a change for a better world.”

“A Common theme would be Unity and Solidarity. Music has the unique ability to bring communities together who share common beliefs and experiences. Certain genres have the ability to weave narratives of togetherness and unity, which provides a sonic backdrop for movements advocating for social cohesion and shared values. In times of social upheaval, these musical expressions serve as unifying forces, bringing people together under the umbrella of shared aspirations for a better world.’

Music Theory

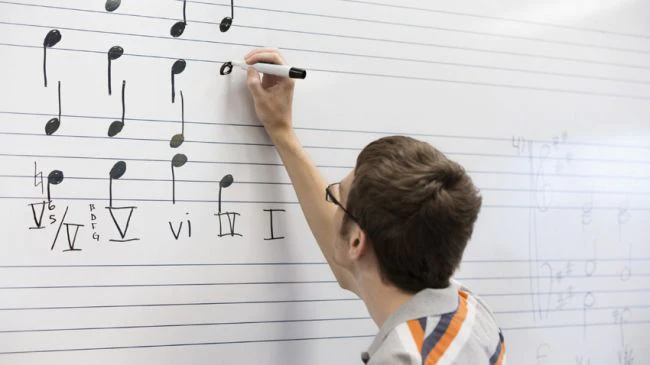

In his 2019 paper; “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame” music scholar Philip Ewell states that the way music theory is taught in most European and North-American musical institutes is an example of the way in which 18th century European Classical music is seen as the norm. If you study music in a conservatoire in Europe or North-America, you will probably come in contact with the music analysis theory by Heinrich Shenker (1868 – 1935).

The Shenkarian theory analyzes music through the basic principle of the V-I harmonic connection. The theory states that all harmonic progressions are linked to this basic principle and that all music can be analyzed through this method. The theory suggests that the value and legitimacy of a musical composition can be tested through this theory.

The idea of Schenker of testing music for its objective value through one standardized method does not come out of nowhere. Schenker explicitly believed in the hierarchy of people and had notably racist and supremist thoughts. There are many examples of him looking down on any other music than works of 18th century German composers, or ‘German Geniuses’ as he called them.

The Shenkarian theory is in many conservatoires the backbone of how music theory is taught. Not only in classical music, but also for music styles that have their cultural roots outside of western Europe, even though this music in some ways does not make sense when analyzed through this theory. For example: The traditional Indian Raga music is harmonically mostly based on ‘thaat’, a scale system similar, but not comparable, to that of the church modes system that we know from western music theory. Yet, analyzing these ‘thaat’ through this western view is in theory possible, it will never really make sense and it will per definition never fully grasp the music’s intentions. Youtuber and music journalist Adam Neely compared it to learning a language. He states that, if you would choose to learn a new language, you wouldn’t start with learning the basic grammar of a totally different language. Music conservatoires using these theories as a basis of their students’ musical understanding is in essence exactly doing that.

The controversy around the study of Philip Ewell is an example of music as a mirror of historical, political and cultural change. The study challenges the music world to rethink the principles of how we think about music and music theory.

Baraye: For the Sake of Change in Iranian Protests

After the revolution against the royal monarch in 1979, the state of Iran introduced a mandatory dress code for women, which is in accordance with the Islamic religion and customs. This was the ‘Abaya’, a garment that literally covers the whole body, head, and hair, except for the face, hands, and feet. This garment is also called ‘hijab’. On the 13th of September 2022, Mahsa Amini was arrested by Iranian police for not wearing her hijab properly. On the 16th, three days later, she left her last breath in the hospital. Many rumours were spread after this, but witnesses of Mahsa’s mistreatment revealed that the cause of her death was the violence by the police (which they never admitted to). The reporter who broke the story of her torture and murder, Niloofar Hamedi, was arrested. After the murder of Mahsa Amini, people in Iran felt that it was the last drop of injustice, and a revolution started.

The song “Baraye” became the anthem of the Iranian human rights protests of early 2022. In this song reasons for resistance are summed up. Baraye (‘because of …’, or ‘for the sake of …’) explains the different facets of the human rights issues through the eyes of young people living in Iran. Through social media the song became a widespread symbol for powerful protest and hope for a better future. The importance of the song for the people of

Iran comes to light even more by the fact that the composer of the song has been arrested for posting it on the internet.

The nomination for a Grammy in the ‘songs for social change’ category, gave the song widespread attention in the western world. Yet, the nomination is seen by some as an easy way out for the western world to seemingly contribute to the actual social change it evokes in Iran. The actual impact and contribution to the fight for human rights through a nomination like this is a serious point of discussion.

In Iran and its turbulent situation, a song is out there to make people outside of Iran aware of the situation and the dangers of the current regime; even if they tried to hide it and destroy its power, it emerged even greater. In this way, Baraye is an example of how music can function as an implicit or explicit commentary on power. Anthem songs have changed completely over the years. The song that was considered the anthem of the 1979 protests was more violent, a march, a huge stomp for people to hear. ‘Baraye’, today’s anthem for equality and solidarity, is an emotional song, a cry for help, an expression of thoughts and injustice. Its goal is to reach the emotions of the audience. There is a big change in the confrontation and the evolution of those songs, showing us exactly how these people have changed through the years and how they have had enough of instability and violence in their state and country. While music holds this magnificent power, we must never forget that is unfortunately not enough.

The reason we study music and practice it is to help us with our piece of mind and our sense of being, but there is a limit to it. It is great to raise awareness through it, make a statement, create a community. But this should always be the start of the change, not its main event.

Gnawa Culture

In Gnawa, an ancient Sufi brotherhood music practiced in Morocco all-night rituals serve to unite the community. The music is ritualistic, spiritual. It is performed constantly, and the rituals that rely on it might even go on for days. It involves Moroccan percussion such as karkabas (a form of crotales), tbel (a form of drum), guembri (a form of guitar) and voices. Dance also plays a big part in the ritual. The rituals are open for everyone; the fact that everybody in the community participates in the musical action can teach us a lot about community and understanding of art.

Music and Dance are not just forms of leisure for the Gnawa, they are also an important part of their identity. There can be no identity or ‘normality’ for them without the connections they make with the spiritual world; those connections are deeply connected to playing music and singing. The rituals are taking place in large groups, they are demanded by individuals who also participate; the events are open and shared. Even if the person who demands the ritual wants it to be more intimate, the people of the Gnawa groups and tribes can still participate in it.

Gnawa tribes have traveled from Morocco to Europe for years now, and they have been established mostly in Belgium, specifically Brussels. There are at least two important groups there. Those groups have settled nicely, having been ‘accepted’ by the Belgian society without losing their roots or identity. They have managed to continue their tradition, their relationships and their heritage without being excluded from the people. Each country’s residents have welcomed them and honored their tradition and customs.

The oral transmission of their musical tradition is a predominant method of perpetuation within the community. Everybody is allowed to take part, but the leader of the ritual is always an experienced member. Rhythm is extremely important, as are the words.

The Gnawa people have faced considerable hardships, and it’s not entirely clear where they originally came from – possibly Morocco or Sudan, perhaps as slaves. Despite this uncertainty, one thing that binds them together, both symbolically and literally, is their shared love for music. It is used as an art, as remedy, as help, as solidarity. Their identity is defined and saved by it. It is beautiful, strong, and helps each generation without holding them back to a ‘dead’ tradition. It is truly a wonder and incredible to witness the rituals and learn from them, see how the people interact and how connected they are to sound and movement.

Kaapse Klopse

The Kaapse Klopse Carnival of Cape Town, South Africa.

The Kaapse Klopse is also known as the Cape Minstrels and is rooted in the Cultural Tapestry of Cape Town, South Africa. This tradition is vibrant and dynamic; it embodies the spirit of celebration and resilience. This is an event that happens annually with origins dating back to the time of slavery early in the 19th century. The event has evolved into an expressive and colorful Carnival which is celebrated on the 2nd of January every year and is also known as “Tweede Nuwe Jaar ”. This day is said to have been the day that Cape Slaves had time off while New Year’s day was a working day for the slaves as the slave owners celebrated.

However, “Tweede Nuwe Jaar” is not the only day that is celebrated. The Carnival period is stretched over a longer time period beginning in early December and finishing in late March early April. Along with the Carnival there are other accompanying aspects that are happening too, like the Nag troupe (Malay Choirs) and Christmas bands/Christmas choirs. Which all fall part of the festivities in Cape Town. The Kaapse Klopse is characterized by the lively parades featuring elaborately costumed troupes playing vibrant music to beat of the Ghoema drum and highly spirited dancing. The Klopse proudly showcase their cultural identity with flamboyant brightly colored satin outfits adorned with intricate beadwork and feathers. Beyond its festive exterior ‘The Kaapse Klopse’ Carnival holds deeper historical significance as it represents the resilience and tenacity of communities who, despite historical adversity, have embraced this cultural expression as a means of celebration, unity and defiance. The Carnival’s music is a blend of traditional African rhythms, military band influences, popular music and local Cape Jazz. Which further underscores the diverse heritage of Cape Town. The Kaapse Klopse stands as testament to the power of cultural expression in fostering community pride, preserving heritage and contributing to the rich history and mosaic of South African identity.

In many cultures, people embrace their tradition, their songs and their customs, incorporating them into their own life. In South Africa music is part of communal practices, it helps the people remember what they have been through and what they are fighting towards, without losing its identity as a collective event that is there to connect and be celebrated.

Conclusion, connecting the different topics and domains

In the case of the people in Cape Town, as well as the Gnawa people, music is such a big part of their culture and everyday life, that it is impossible to separate it as a different entity. They are the music, they learn through it, they use it as a tool and as part of their families and communities. Their music helps us understand them from an outsider’s perspective.

For these cultural groups from Morocco and South-Africa music has become the vehicle for marginalized communities to reclaim and celebrate their cultural identities. The different musical genres not only showcase their unique musical traditions or specific cultures, but it also touches on addressing social issues and advocating for change. Artists within these genres often use their platforms to mix the cultural roots with contemporary themes, creating a dynamic fusion that resonates with both their heritage and the current social context.

The crossover of cultural identity and pride within music is a powerful force for social change. This serves as a means for cultural preservation, resistance against oppression, and a celebration of diversity. As musicians and artists navigate the complex interplay between tradition and contemporary expression, they not only shape the cultural landscape but contribute to a better society where the diverse identities and cultures are embraced and celebrated and used altogether to progress collectively.

Cultural identity and pride within music play a crucial role in the realm of social change, serving as powerful tools for both self-expression and the assertion of collective identity. Music has the unique ability to convey the richness of diverse cultural experiences, creating a sense of belonging and pride among individuals and communities. This connection between music, cultural identity, and social change is a dynamic interplay that has been evident throughout history.

In Iran, things are way different. Music is a voice that rises when needed, a separate event. It is only the beginning of a revolution, an anthem that gives the tempo, a way of communicating not only with each other but also with the world around them. A scream for attention and necessity. When it comes to actual, active change about social matters,

______

‘Baraye’ is an example of an anthem, a piece of music that succeeds in getting the attention it and the situation deserve: it won a Grammy for the new category ‘Music and Social Change’. However, the discussion is still open as to how much this award for change actually contributes to said ‘Change’. The people know, they are aware, they are emotionally affected. But if the power of the song (and subsequently the award) is big enough to constitute actual political change is yet to be seen. One thing is for sure: it is a big win for artists around the globe, but the fight is far from over.

___

Music has been a powerful tool throughout history for expressing social change and influencing cultural movements. Various common themes have emerged in the intersection of music and social change. Music and social change share an interesting relationship with artists, with artists often being at the forefront as cultural architects in shaping and reflecting on view points and issues of their time. A common theme that resonates across various musical genres is protest and activism. Throughout history musicians have used their platform and power of their art to shed light on topics, to challenge authorities and call for social changes to take place. Protest songs like “Baraye” have become anthems for the Iranian human rights protest. This anthem resonates with different generations which acts as a backdrop for the enduring power of music to voice their collective injustices.

References

Literature

Davids, N. “ ‘It is us’: An Exploration of ‘Race’ and Place in the Cape Town Minstrel Carnival.” TDR 57, no. 2 (2013): 86–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24584795

Baxter, Lisa. “History, identity and meaning: Cape Town’s Coon Carnival in the 1960s and 1970s.” MA thesis, University of Cape Town, 1996. https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/19684

Ewell, Philip A. “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame.” Music Theory Online 26, no. 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.2.4.

Inglese, Francesca. “Choreographing Cape Town through Goema Music and Dance.” African Music Journal 9, no. 4 (2014): 123–145. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24877356.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A61c88f5000691fb0f7a819064bb34cf6&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1

Marks, Emmy Jean. The Role of Social Media in Iran: Finding Community through the Death og Zhina (Mahsa) Amini. Compass (2023). Vol. 3, Issue 1, p. 20-27. https://doi.org/10.29173/comp74

Martin, Denis-Constant. Sounding the Cape: Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. Cape Town: African Minds, 2013. https://www.africanminds.co.za/sounding-the-cape-music-identity-and-politics-in-south-africa/

Mashayekh, Sara. “Baraye: Understanding Iran’s Song of Protest and Compassion.” Ajam Media Collective. February 9, 2023. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://ajammc.com/2023/02/09/baraye-irans-song-of-protest/

Witulski, Christopher. “Contentious Spectacle: Negotiated Authenticity within Morocco’s Gnawa Ritual.” Ethnomusicology 62, no. 1 (2018): 58–82. https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.62.1.0058.

Video’s

AfroArtistaFilms. “The Coloureds (South Africa): The Most Genetically Mixed Race on Earth.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/NOWPDhErMD0?si=SAgO1ZF9gor5fIEn

AJ+. “Apartheid explained.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/S7yvnUz2PLE?si=Xoon8JbERMPHChHz

AlJazeeraEnglish. “How the Carnival Affects Community Members.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/Ia29Gq29An0?si=e-FcibBfiUQkhtQa

Beautiful News. “The Face Painter at the Heart of Cape Town’s Kaapse Klopse Carnival.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/kJJz_w3ut3g?si=GE3Sxpr4UCWV-k7Q

Jephta, Benjamin. “Born Coloured not Born Free.” Videoclip. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/kbgRPNQXdBA?si=YuXSBhjyuDJAOGIF

Neely, Adam. “Music Theory and White Supremacy.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kr3quGh7pJA&t=929s

News24. “The Cape Town Family Who’s been Painting Klopse Faces for over a Decade.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/MSjlaDL6AN8?si=uKDzJNE5fDDPpkd6

Saïd Akasri, Mohamed and Driss Filali. “Gnawa Music and Dance.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://muziekpublique.be/lessons/gnawa-muziek-en-dans/?lang=en

Masaman. “The Fascinating History and Genetics of the Cape Coloureds of South Africa.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/KsIDoPepcI8?si=lV4KcbD57L3zX0pq

Viator Travel. “District 6 community Cape Town.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://youtu.be/ZdojQj2dYes?si=RjYwHPGR0AC-z9SI